Biodiversity credits explained: Mechanics, markets and use cases for investors

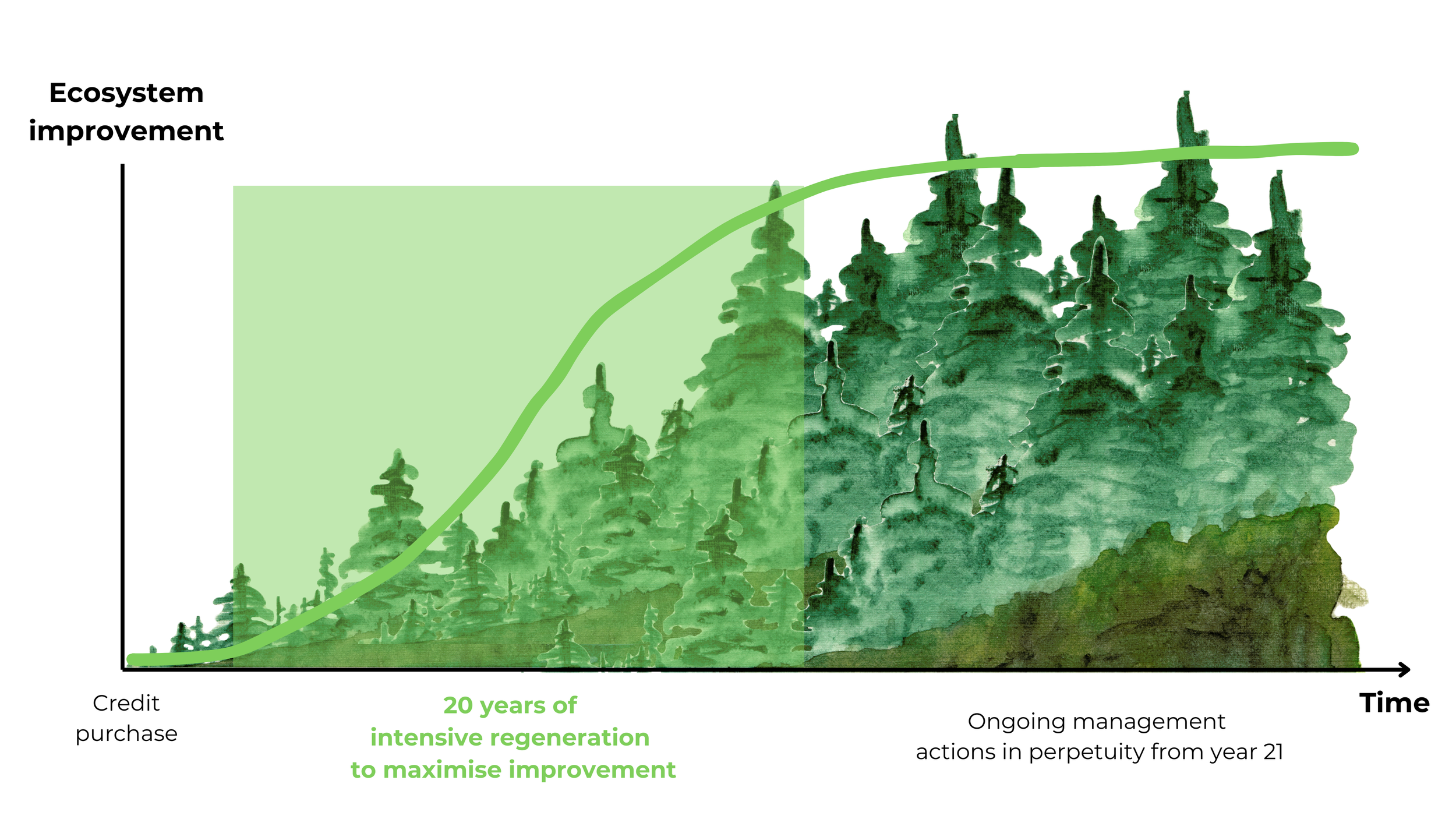

Image shows a case where credits are associated with active restoration over a 20 year period and site is maintained in perpetuity.

In recent years biodiversity credits have gained prominence, attracting growing attention at major global forums like the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)’s World Conservation Congress held in Abu Dhabi in early October 2025, and COP30 held in Brazil in November 2025.

But biodiversity credits are not new. In fact, the first US Wetland Mitigation Banks were established to produce biodiversity credits (known as ‘wetland mitigation credits’) in the early 1980s. This predates the first carbon credit project, which followed in 1988.

Despite being overshadowed by developments in carbon markets, Bloomberg NEF estimates that biodiversity credit markets will grow to USD$160B by 2030. Market growth will inevitably bring new investment opportunities and biodiversity credit markets are already attracting the interest of both private investors and fund managers.

So what exactly are biodiversity credits? How do they work? And how can investors get involved?

What’s in a credit?

The World Economic Forum defines a biodiversity credit as “an economic instrument used to finance activities that deliver net positive biodiversity gains”. In practice, biodiversity credits (sometimes called certificates) represent a specified unit of uplift in ecological condition over a specific area, maintained for a specific time period. For example, a biodiversity credit may represent 1% uplift in ecological condition over 1ha of land, maintained for 100 years.

Biodiversity credits issued under different schemes and/or operating in different jurisdictions can vary considerably, offering more or less biodiversity. Some of the key characteristics investors should consider when it comes to biodiversity credits include:

Conservation area: Credits may refer to ecological uplift over a large (1ha) or a very small area - even down to 1m2 (as, for example, in the case of Wilderlands voluntary markets credits in Australia).

Source of ecological uplift: Credits may be issued where ecological uplift occurs as a result of active site restoration works, maintenance activities that prevent site decline from weeds or other threats, or preservation. Given the legacy of ecological loss, restoration activities that expand viable species habitat will be crucial, and, given the cost of restoration works, credits that deliver restoration works are likely to be associated with a higher dollar value. Preservation of existing habitats is also important, but credits should only be issued where a high risk of land clearing in the absence of protection can be demonstrated.

Additionality: The extent to which the purchase of a credit triggers conservation works that would not have otherwise occurred. Credits should only be only issued for the ‘additional’ ecological uplift that is delivered as a direct outcome of the conservation works funded by the sale of credits (not for pre-existing biodiversity at the site).

Stand-alone, green carbon, bundled or stacked: Biodiversity credits can be sold as a stand-alone product, or as an ‘add-on’ to carbon credits - whether as a ‘green’ element that attracts a price premium, or sold explicitly as as an additional, measured outcome from the same (stacked) or separate (bundled) conservation sites. Under some circumstances these arrangements may limit the additionality of biodiversity credits, so caution should be applied when investing for maximum ecological impact.

Conservation period: The conservation period covered by a specific biodiversity credit can range from one year to in perpetuity protection.

Given the size of the investment required to achieve the world’s global biodiversity targets, there is a place for all different types of biodiversity credits to contribute. But investors need to be aware to compare on an equivalent basis. For example, it may be useful to convert different credits to the same conservation area and conservation period basis and consider cost-effectiveness of each dollar spent on different credit types. A detailed study by Skjander’s founder in 2024 compared various biodiversity credits and found there can be enormous variation in the biodiversity return per dollar spent.

How are credits used?

Biodiversity credits currently underpin two different types of markets: compliance and voluntary markets.

In compliance markets, demand for credits is mandated through legislation. Developers are required to purchase biodiversity credits to offset their biodiversity impacts as part of formal development approval processes. A number of mature, high value compliance markets for biodiversity already exist: the USA’s Mitigation Banking, Australia’s Biodiversity Offsets Scheme and the UK’s Biodiversity Net Gain units all provide compliance-grade credits that are used for regulatory offsetting, with estimated combined annual turnover estimated to be in excess of USD 5.5B. An additional 40+ compliance markets are newly operational or in development around the globe.

In voluntary markets, there is no legal requirement for buyers to acquire biodiversity credits. Voluntary biodiversity credit purchases are sometimes described as ‘non-compensatory’ because they aren’t used explicitly as an offset for biodiversity loss. Purchases of voluntary biodiversity credits to date have mostly comprised philanthropic or corporate donations. The latter is usually a means of mitigating indirect corporate impacts on biodiversity for reputational purposes. Voluntary biodiversity markets are currently very small. Estimated market turnover to date is in the order of $10M - based on Bloomlabs data. This places total trade in voluntary biodiversity markets since inception at less than 1% of annual compliance market turnover.

How can investors get involved?

The largest existing biodiversity credits investment opportunities are based in compliance markets. The nature of the investment opportunity depends on the specific market of interest. In some cases, investors can invest directly into credits - either by purchasing credits themselves or investing into a fund that can provide access to a diversified portfolio of credits. In other cases, they can invest into the land and on-ground restoration works that generate economic uplift and associated credits (read more on this in our post comparing biodiversity offset markets in Australia and the USA). Both of these investment options can deliver a good return on investment under the right conditions. As an example, long-term price trends in the biodiversity credits held in Skjander’s first portfolio suggest growth upwards of 15% per annum.

Investment into voluntary markets has so far been limited. We expect demand for voluntary biodiversity credits to increase through time as companies seek to meet consumer environmental demand and address their biodiversity impacts using reporting frameworks like the Taskforce for Nature-related Financial disclosures (TNFD) and the Science-Based Targets Network (SBTN). Even so, we expect voluntary markets will only ever be a small part of the overall biodiversity markets. We expect that larger investments by corporates are more likely to arise from new regulatory requirements.

In a market set to grow to USD$160B by 2030, new modes of investment that support the delivery of biodiversity credits at scale are sure to emerge. Watch this space.

References

Bloomberg NEF. (2024). Biodiversity Finance Factbook. https://assets.bbhub.io/professional/sites/24/Biodiversity-Finance-Factbook_COP16.pdfk

Bloomlabs. (2026). Market intelligence for biodiversity credits. https://app.bloomlabs.earth/

Chandrasekhar. (2023). Timeline: The 60-year history of carbon offsets. https://interactive.carbonbrief.org/carbon-offsets-2023/timeline.html

Environmental Defense. (1999). Mitigation banking as an endangered species conservation tool. https://www.cbd.int/financial/offsets/usa-offsetspecies.pdf

Heagney & Nolles. (2024). The cost of biodiversity - what nascent biodiversity markets are telling us. https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/cfa07821-39f0-4678-a173-e05e73b884d6/downloads/pricing_of_biodiversity%2020240403.pdf?ver=1762121583296

Science Based Targets Network. (2026). https://sciencebasedtargetsnetwork.org/

Skjander. (2025). USA vs NSW - Comparing two biodiversity market trailblazers. https://skjander.com/blog/usa-vs-aus-biodiversity-markets

The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures. (2026). https://tnfd.global/

World Economic Forum. (2022). Biodiversity credits as an economic instrument. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2022/12/biodiversity-credits-nature-cop15/

BloombergNEF. (2023). Biodiversity Markets Primer: Credit Where It’s Due. https://www.bnef.com/insights/31421

World Economic Forum (2022). Biodiversity Credits Markets Integrity and Governance Principles Consultation. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Biodiversity_Credits_Markets_Integrity_and_Governance_Principles_Consultation.pdf

Wunder et al. (2025). Biodiversity Credits: An Overview of the Current State, Future Opportunities, and Potential Pitfalls. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/bse.70018